Project Report | April 10, 2019

Bonefish Spawning in the Bahamas

Capturing the Dynamics & Behavior of a Paramount Recreational Fishery Species at a Critical Period in Their Life History

PI:

Aaron Adams, Ph.D. (Bonefish and Tarpon Trust; Florida Atlantic University, Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute)

Co-Investigators:

Matthew Ajemian, Ph.D. (Florida Atlantic University, Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute)

Sahar Mejri, Ph.D. (Florida Atlantic University, Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute)

Paul Wills, Ph.D. (Florida Atlantic University, Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute)

Jon Shenker, Ph.D. (Florida Institute of Technology)

Background

Bonefish are economically important throughout their range. This is especially true in The Bahamas, where the annual economic impact of the recreational bonefish fishery exceeds $141 million, supporting thousands of jobs. Indeed, on many of the out-islands, the bonefish fishery accounts for nearly 50% of island economies. The bonefish fishery is also culturally important – the skill of being a fishing guide is frequently passed along family lines. Similarly, bonefish contribute to the flats fisheries that have an annual economic impact exceeding $465 million in the Florida Keys, and $50 million in Belize. Economically important flats fisheries also occur in Mexico, Cuba, and other locations in the Caribbean, but studies to document the economic impact have not been conducted. The economic importance of bonefish has led to the creation of strict regulations to protect the fishery in some countries: bonefish are catch and release only in Florida, Belize, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. In other locations, the recreational catch and release fishery coexists with consumptive fisheries that are subject to varying levels of management. In The Bahamas, capture with nets and commercial sale are illegal, but harvest with hook and line for personal consumption is allowed. The recreational flats fishery in Cuba occurs within marine protected areas designated as recreational catch and release zones, outside of these zones there are no regulations on what appears to be an intensive net fishery with high harvest. In addition to their fishery value, the abundance of bonefish in shallow coastal habitats, the dominance of benthic invertebrates in their diet, and their role as prey for sharks and barracudas suggest that bonefish play an important ecological role in structuring tropical shallow-water food webs. Recent and ongoing research provides a general understanding of the bonefish life cycle. Adults exhibit high home range fidelity to shallow flats habitats of sand, seagrass, mangroves, and hardbottom during non-spawning time periods. Adults undergo migrations to pre-spawning sites – shallow protected bays immediately adjacent to deep water – between October and April. Bonefish aggregate at pre-spawning sites before moving offshore at dusk to spawn at night, with putative spawning occurring at depths >50m at or near deep-water drop-offs (>1000 m total depth), before fish return to their shallow water flats habitats. Once larvae hatch from the eggs, they live as plankton in ocean waters for 41 to 71 days. Surviving larvae metamorphose into juveniles and use sand or sandy mud bottoms in shallow, protected bays adjacent to deeper water channels that provide larval access and are near eventual adult habitats. An International Union for the Conservation of Nature assessment classified bonefish as Near Threatened due to habitat loss and fragmentation (particularly mangroves and seagrasses), coastal development and urbanization, declines in water quality, and harvest by commercial, artisanal and recreational fisheries. In Cuba, for example, there is intense harvest of multiple bonefish pre-spawning aggregations (PSAs), with estimates of up to 20 tons harvested annually. In the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico, fishers have traditionally targeted purported bonefish spawning migrations. In locations with recreational fisheries and no commercial harvest, the chief concern is habitat loss and degradation, though illegal harvest and lack of enforcement are also threats. For example, the top threats to bonefish in The Bahamas are habitat loss, habitat degradation, and illegal harvest of bonefish for commercial sale using nets. Habitat loss and degradation are caused by coastal development. Two of the PSA sites identified in The Bahamas, for example, have been proposed as sites for deepwater ports/marinas. Harvest is most common along spawning migration pathways. Threats to PSA sites are especially worrisome. Because individuals from a large geographic area are highly concentrated at PSA sites, these spawning aggregations and their associated populations are especially vulnerable to human impacts such as overfishing, and habitat degradation and loss. Loss of productivity due to harvest or habitat disturbance at a localized aggregating site may have population-level consequences. For example, harvest of fish from spawning aggregations has caused regional population declines for Nassau grouper and other species, and coastal development has impacted Nassau grouper spawning sites in the Mexican Caribbean. Similarly, construction of causeways that disrupted bonefish spawning migrations on Kiribati have contributed to the cessation of spawning at numerous sites, and changes in bonefish population demographics. Population declines from impacts on spawning aggregations may be preventable with a more thorough understanding of movement patterns associated with spawning aggregation formation, and identification of pre-spawning and spawning sites that result in conservation actions to protect the aggregation sites. Important spawning aggregation sites have been effectively protected in some locations (e.g., red hind in the United States Virgin Islands). Indeed, research has even been conducted to identify spawning sites proactively for heavily harvested snapper and grouper species – prior to fisheries exploitation or habitat degradation – to inform conservation for commercially important species.

Research Needs

Recent research of bonefish using oceanographic and genetic approaches revealed high levels of connectivity of bonefish populations throughout the Caribbean. This means that when bonefish spawn, a significant portion of their larvae are transported to other locations. Thus, spawning at one site likely provides larvae to sustain the local population, but also supports different populations. For example, some of the larvae spawned on Abaco will settle on Grand Bahama and Andros. Thus, identification and protection of PSA sites has regional conservation implications. However, there is a shortcoming to the estimate of larval transport using oceanographic models. We don’t know the behavior of bonefish larvae. Research on other species shows that fish larvae are able to migrate vertically in the water column, which exposes them to different currents. Larvae at 60m depth, for example, may be exposed to different currents than those at 5m depth. Since we don’t yet know bonefish larval behavior, the oceanographic models used to estimate transport of bonefish larvae assume the larvae are passive particles near the ocean surface. Although not entirely accurate, this gives us a reasonable approximation of larval transport. Research is needed to determine the behavior of bonefish larvae. The most effective way to achieve this is by rearing larvae in captivity. Recent research on bonefish hormone levels and egg development has provided a better understanding of bonefish reproductive physiology. However, this research has only laid the foundation – much more work is needed. For example, blood samples to obtain hormones and egg samples to evaluate egg development have been collected at only a few locations. And preliminary data reveal differences among locations. And though recent research has revealed much about egg development during the pre-spawning aggregation period, considerable variation has been observed. Therefore, more research is needed to more fully develop our understanding of bonefish reproductive physiology.

Research Focus

The purpose of research cruises aboard the M/Y Albula, supported by the Fisheries Research Foundation, has been to fill information gaps of the bonefish life cycle to improve conservation. Specific objectives in the 2018-2019 were:

- Identify new PSAs, confirm reported PSAs, and better determine the lunar phases of spawning

- Obtain a better understanding of the bonefish offshore spawning process

- Document links between the PSA sites and bonefish home ranges to better understand the geographic scope of importance for PSA sites.

- Induce bonefish spawning in captivity testing multiple reproductive hormone injection types and methods

- Successfully hatch and rear bonefish larvae to enable research on larval behavior, ecology, and diet

- Examine endocrine and sex hormone levels in adult females and determine egg development to understand the reproductive biology and physiology of bonefish.

Research Results

PSA Identification and Offshore Tracking

We encountered large PSAs of bonefish (more than 5,000 bonefish) on the first study day (November 18, 2018) at that Abaco site. On two successive days, we captured 3 bonefish from the PSA, and surgically implanted each fish with acoustic tags that emit continuous ultrasonic pings. We used a boat-mounted acoustic receiver to detect the pings, which allowed us to follow the fish as they moved offshore to spawn. The following night (November 19), we successfully tracked bonefish from dusk, when they moved offshore, to 5:00 am, when they descended to spawn. This track was unprecedented in multiple ways:

- The distance the fish migrated from the nearshore pre-spawning site to the offshore spawning site (approximately 8 miles) was longer than any previous tracks;

- The distance from shore of the spawning site (approximately 3 miles) was farther offshore than previously documented;

- The depth to which the bonefish descended to spawn (approximately 200 feet) was deeper than previously documented;

- The total water depth at the spawning site (approximately 5,000 feet) was deeper than previously documented.

Depth of tagged bonefish (meters) during the offshore movement and descent to spawn

Following the process described in a recent scientific article (Adams, A.J., J. Shenker, Z. Jud, J. Lewis, E. Carey, A.J. Danylchuk. 2018. Identifying pre-spawning aggregation sites for bonefish (Albula vulpes) in the Bahamas to inform habitat protection and species conservation. Environmental Biology of Fishes), we confirmed a bonefish PSA site on Long Island. The month and location of the cruise was based upon reports from local fishermen (recreational, subsistence, and commercial fishermen), who reported seeing large schools of bonefish at this site during grouper spawning season (which is typically the full moon of January, and secondarily February). This information has been entered into the BTT bonefish spawning database, and has been shared with Bahamas National Trust. Previously identified PSA sites have either been included in newly designated national parks or have been proposed for protection by Bahamas National Trust. Pre-spawning aggregations were observed on two consecutive days (January 15 and 16, 2019). The fish in these schools exhibited pre-spawning behavior (i.e., porpoising at the surface, compact schools in non-flats habitat, etc.) in the afternoon and evening. However, the bonefish in the Long Island PSAs differed from other locations in numerous ways. First, the PSAs were present for only two days; in other locations, PSAs are active for 3 – 5 days. Second, unlike the PSAs at Abaco and other sites we have sampled, the Long Island bonefish were very skittish, which made it difficult to follow the schools. In addition, all of the fish we captured from the PSAs were either males or sex could not be determined. One of the requirements for tracking PSAs offshore is that at least one of the three fish we tag is a female. This ensures that we are tracking fish that spawn. Since we did not capture any females from the PSAs, the skittish behavior of the fish made it very difficult to maintain contact with the fish, and the PSA was only present on two days, we did not track fish on this research cruise. The lack of females in our samples may have been due to a skewed sex ratio (possibly due to illegal netting that targets large fish) or just bad luck during sampling. Nonetheless, a new PSA site has been confirmed, and will be studied in future trips to Long Island. A new PSA site was also identified at Bimini, again at a location that was a suspected PSA site based on interviews with fishing guides and fishermen. Tracking of bonefish during their offshore spawning migration was unsuccessful, possibly due to predation of the tagged fish by sharks. Unfortunately, bad weather forced the termination of the cruise after the first night the PSA was observed, precluding additional tracking.

Map showing where bonefish were tagged (yellow ovals) and the location of a newly identified PSA site on Bimini.

Flats – PSA Site Connectivity

More than 400 bonefish were tagged with dart tags on both the flats and within the PSAs to determine the spatial extent of connectivity between the PSAs and bonefish home range: in other words, from how far do bonefish migrate to reach a PSA, what is the regional importance of a PSA? Already, a recapture has occurred. One of the bonefish tagged at the Abaco PSA in November was recaptured by a fishing guide and his client on January 15, 2019, on a flat in the Abaco Marls. The distance between the PSA and the recapture location was 65 miles. We anticipate additional recaptures of tagged bonefish in the coming months.

Bonefish tagged at the Abaco PSA site in November 2018, recaptured January 15, 2019, in the Abaco Marls.

Tagging locations and PSA search areas at the Berry Islands.

Spawning Induction

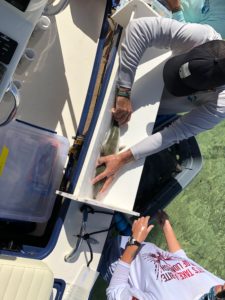

Bonefish collected from PSAs were successfully spawned on two occasions – in Abaco and Bimini. The initial cruise to Abaco in November 2018, was designed to test our on-board holding tanks for adult fishes and our egg/larval incubation systems. This first cruise, to a PSA site where we had previously worked, proved to be a great success. A total of 16 bonefish (6 males, 10 females) was collected from PSA and placed in the polyethylene tanks (5’ diameter) on the foredeck. All collected bonefish were spawning-ready. Fish were held in tanks for no longer than 3 days in the 1,500 L flow through tank system on the foredeck, and exposed to ambient conditions.

Tanks on the foredeck for captive spawning.

Since removing fish from the wild and placing them in captivity typically induces some stress and might disrupt the natural reproductive process, we used injections of hormones to induce the fish to continue through the spawning process. All females that received injections, had oocytes (eggs) larger than 700 um with a visible central nucleus (germinal vesical (GV)). From all successfully spawned females, before fertilization, egg size in the ovary increased following the first injection of Carp Pituitary hormone Extract (CPE), as egg development advanced through the late vitellogenic stage (LV – yolk-formation stage). Development was also observed where the central germinal vesicle migrated to the periphery of the egg (germinal vesicle migration (GVM)), followed by dissolution of the nuclear membrane (germinal vesicle break down (GVBD)) and filling with water (hydration) just before ovulation. Four of the females produced eggs viable for ovulation and thus spawning.

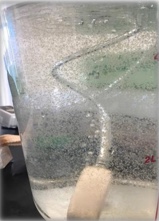

The figure above summarizes the histology results showing steps of oocyte (egg) final maturation following hormonal (CPE) injection. First, the germinal vesical (GV) is central. Second, the germinal vesical migration (GVM) occurs, followed by the germinal vesical break down (GVBD) and hydration (HYD) before ovulation and spawning. When the females began emitting small amounts of eggs on their own, the females were considered ready to spawn and therefore “strip spawned” to collect the eggs, and mixed with sperm from the males (strip spawned as well). Strip-spawning is a process in which gentle pressure is applied to the fish’s abdomen from front to back to force eggs and sperm out. The eggs were collected in a bowl, and sperm was added and mixed with water to allow fertilization. Eggs were then strained from the excess sperm and placed in hatching jars maintained in the lazarette of the ship.

Picture showing the process of egg fertilization in bonefish: sperm is added gently and mixed with eggs to allow the fertilization process.

We used the same process for 3 bonefish captured from the PSA on Bimini in March 2019. However, fertilized eggs stopped developing and died approximately half-way through development.

Hatching and Rearing

On Abaco, fertilized eggs were moved to the Lazarette, and placed in hatching jars. Eggs hatched 25 to 28 hours post fertilization. The development of the larvae was documented through 66 hours, the last larval bonefish died between 66 hours and 90 hours post-hatch. The documented time of 66 hours is the longest a bonefish larvae ever survived in captivity. The larvae had used up almost all of its yolk, so would have started to feed in the next day or two. Although the larvae mostly suspended motionless in near the water surface, they did begin to show movement with short bursts of movement.

Reproductive Physiology

More than 100 blood and egg samples were collected from female bonefish on Abacos, Long island, Berry Islands, and Bimini. These samples will allow us to determine the stage of development of eggs, their reproductive hormones and the nutrients available to the embryos in these eggs.

Blood being drawn for hormone analysis.

Eggs being obtained by cannulation.

In previous research conducted by our group, we found that across all islands investigated in the Bahamas, significant differences in concentration of sex hormones (17ß-estradiol and testosterone) were observed. Additionally, comparisons between flats and PSAs within islands revealed that the concentrations of these hormones were significantly higher at the PSA compared to flats habitat, confirming our hypothesis that preparation for spawning starts at the flats, and continues at PSAs before spawning. Moreover, when investigating egg development in correlation with sex hormone levels, we found that all fish sampled at PSAs were spawning capable with 88.6% of spawning capable fish showing evidence of germinal vesicle migration (GVM) or breakdown (GVBD). Conversely, 29.0% of fish sampled along the flats were spawning capable with only 3.1% exhibiting evidence of GVM or GVBD. The preliminary analysis of samples taken on the M/Y Albula cruises confirm this general pattern, but show differences among islands.

Map showing the presence of 100% spawning capable females in the PSAs and a mix of developing, regressing and immature females at flat locations, based on the histological analysis of oocytes collected at these sites.

Sex hormone levels (Estradiol and testosterone) form spawning capable females in the PSAs (red circle) and females from the flats showing higher levels of these hormones at PSAs locations.

Conservation Applications

A top need for conservation of fish species that aggregate to spawn is identification of spawning sites so that these sites can be protected. Indeed, the realization that identification and protection of fish spawning aggregations is of vital conservation value was the impetus behind the Science and Conservation of Fish Aggregations (SCRFA.org). The challenge is to identify these sites in a timely and cost-effective manner. The research cruises supported by the Fisheries Research Foundation are helping to address this challenge. One of the great challenges to conservation of bonefish and other tropical fish species that aggregate to spawn is that most exist in data poor situations. There has never been a stock assessment of bonefish, for example, and only recently was the first scientific documentation of a bonefish PSA was published. Given that even for species, like groupers and snappers, for which data are available, fisheries management for these species still occurs in data poor circumstances, resulting in many overfished populations and conservation challenges. The challenge is double for bonefish – the fishery is and will remain relatively data-poor and will continue to receive less attention from management agencies than commercially valuable species. It is therefore essential to add knowledge of bonefish in a focused manner to allow effective conservation and education. The data being obtained on the M/Y Albula research cruises is contributing to protection of additional sites. Because of the topography of bonefish pre-spawning sites (protected bays near deep water), they are attractive to developers of marinas and ports. Therefore, BTT shares this information with non-governmental organizations, Bahamas government agencies, and our fishery partners for incorporation into management strategies. This has already resulted in the creation of six new national parks on Abaco and Grand Bahama Island for habitat protection. Nonetheless, PSA sites continue to be threatened. Harvest along the spawning migration pathway continues to be reported on Long Island and South Andros. We are using an education approach in an attempt to stop this harvest, with the education platform informed by findings from the research cruises. We’ve also recently learned of a proposed development and marina on the south end of Abaco, immediately adjacent to the PSA site. We are currently involved in discussions aimed at preventing this development since it will likely severely disrupt spawning, which will destroy Abaco’s fishery. Understanding bonefish habitat use and protecting bonefish habitats has broader conservation implications. This is because bonefish is an Umbrella Species (Umbrella species are species whose requirements for persistence are believed to encapsulate those of an array of additional species). The economic and cultural value of the bonefish fishery, as well as the fish’s charismatic characteristics (bonefish regularly appear on fishing magazine covers and are the focus of articles in these magazines), make them uniquely useful to conservation efforts. The benefit from the recreational fisheries perspective is that habitat conservation will greatly contribute to a healthy and sustainable fishery. The benefit to broader conservation is that bonefish provide leverage to situations that might not otherwise gain traction. The information on bonefish reproduction that we gained in the 2018-2019 also has important conservation applications. For example, documenting that bonefish are able to move so far from the PSA site, and spawn miles offshore will help to improve our oceanographic larval transport models. In our original models, spawning locations (the locations where the eggs and larvae initiated their tracks) were closer to the dropoff. Being further offshore might influence the paths taken by larvae and the distance they travel. This adjustment will likely suggest even greater levels of connectivity among islands in the Bahamas, as well as throughout the Caribbean Sea. The data on reproductive physiology – egg development and hormone levels – were the first on bonefish, and provide a first glance at the likely effects of habitat quality on reproduction. The findings on egg development highlight that the location and quality of the habitat and the amount and type of prey could be important determinants for nutrients incorporated into the eggs, which in turn is crucial for egg and larval development and survival. Thus, bonefish conservation should not only focus on habitat protection from development, but also consider the possible effects of degradation on habitat quality. The blood hormone data provide a view into the reproductive process that begins on the flats and culminates in offshore spawning. Following trends in hormone levels during this process will enable us to understand the cues bonefish use to initiate egg production, as well as when to migrate to spawn. This information might make it feasible to focus limitations on seasons as well as locations to ensure that bonefish are able to successfully spawn. Such information would also help to explain why peak spawning months differ among locations. And since the oceanographic currents that transport bonefish larvae vary seasonally and among lunar phases, these data will also help to refine models of connectivity, allowing us to prioritize the most important populations and PSA sites for protection.